The Kemper anecdote, while interesting, isn’t the whole story.

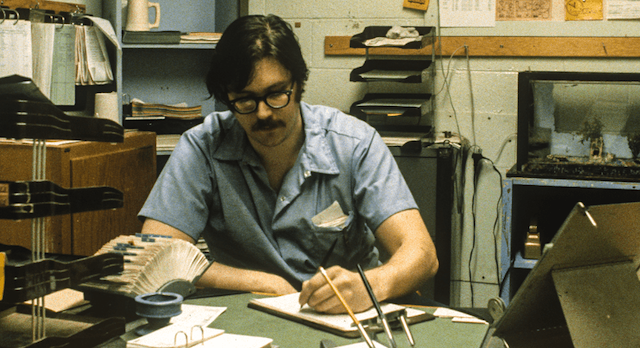

Volunteers of Vacaville (VOV) is a nonprofit organization that began The Blind Project in 1960. VOV’s mission is to help the sight-impaired community worldwide through its cadre of volunteers from local Lion’s Club members, whose biggest project includes glasses donations, teachers for the blind, and community members passionate about the work. The Blind Project is an arm of the VOV that built a partnership between them and and those who are incarcerated at the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s California Medical Facility. The goal is two-fold: being able to provide materials for the blind and visually impaired while also helping rehabilitate the individuals in the prison, providing them an opportunity to learn Braille transcription and Brailler repair, as well as a number of other skills. As the VOV notes on their website, the project is ongoing and has provided hope for both those who are blind, as well as those who are incarcerated. As of early 2018, the VOV notes that the Blind Project has donated 1,099 Braille writers, repairing and refurbishing roughly 400 a year. In 2017 alone, over 9,300 pages of Braille were transcribed for schools across the US. More, recidivism rates for Blind Project workers are less than three percent, compared to the general population of the California Medical Facility. At least one of the former incarcerated Blind Project workers now owns a transcription business of his own. The Kemper story circulated in part due to a 1987 Los Angeles Times story about the Blind Project at Vacaville. The Blind Project, in addition to its work with Braille materials, also records audiobooks for blind and visually impaired, including bestsellers, cookbooks, science fiction, and more. But these materials aren’t for general readers; they’re available only to those who benefit from the VOV project. Kemper was a prolific reader for the project, recording over 5,000 hours as of the Times piece. More recently, one of the Blind Project tasks was to update the recordings done on cassette to CD, making them more accessible with modern technology. All of the audiobooks made are professionally produced, with quality control offered to ensure that stray noises and glitches in the process are removed for end users. Prisoners who are part of the Blind Project work eight hour days, and for many, it gives them meaning. They’re not only learning skills, but they know they’re giving back to those who are most in need of materials like Braille books and recorded audio. The Blind Project has high standards for admitting potential workers. It’s not open to all of those in the prison, and those who do want to be part must pass a number of tests. They also have to not have violence in their records while at the prison, must have a GED or high school diploma, and may be excluded depending on some of the crimes for which they’ve been convicted. Once admitted to the program, there’s extensive training. The Reporter notes, too, that one aspect of the admissions to the program is that interested parties must be able to correctly pronounce the words from a list of 50 and be able to use them in context. The California Medical Facility is one of the state’s medical and psychiatric facilities, though it doesn’t house them exclusively. About one-third of those at the facility are general population, and most of those who are incarcerated at the facility are serving life or very long sentences. According to an article from The Daily Republic, many of those who are involved with the Blind Project see it as a meaningful way to give back after doing significant harm elsewhere. Kemper’s work is well-regarded, and he’s earned more than one recognition for his productions. “I can’t begin to tell you what this has meant to me,” Kemper told The Los Angeles Times about his work with VOV. “[T]o be able to do something constructive for someone else, to be appreciated by so many people, the good feeling it gives me after what I have done.” Toni Ann Gardiner and Ed Eames were two of the beneficiaries of the VOV’s work recording audiobooks. As they told The L.A. Times after a visit to the prison to see the program in actions, “[t]hese prisoners are doing so much for the unseeing population. We just wanted to come here, to meet them and to thank them personally for their dedication to a program that means so much to the blind.” Kemper is no longer part of The Blind Project and hasn’t been since 2015. According to parole hearing proceedings, he suffered a stroke that ended his work with the project. He is still alive and in prison. It’s a sensational story—a serial killer creating audiobooks that are themselves sometimes creepy and disturbing—but, as is often the case with such stories, there is far more worth knowing to it than a splashy headline. In the case of Kemper, the audiobooks he recorded were an opportunity for him to give back to a world he’d harmed. He took the job seriously, much as those who’ve participated in the important work of Volunteers of Vacaville from its inception up until its current projects. The work being done isn’t for general consumption. Rather, this is a story of a project that gives back to a vulnerable population through the work of incarcerated volunteers held to rigorous standards for such a rewarding experience.