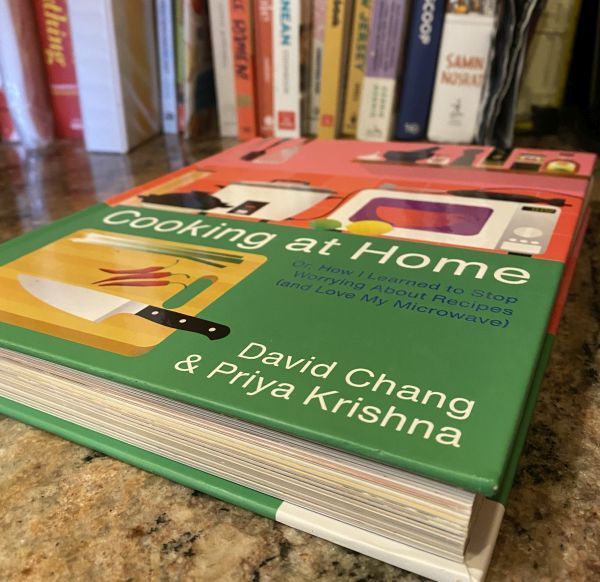

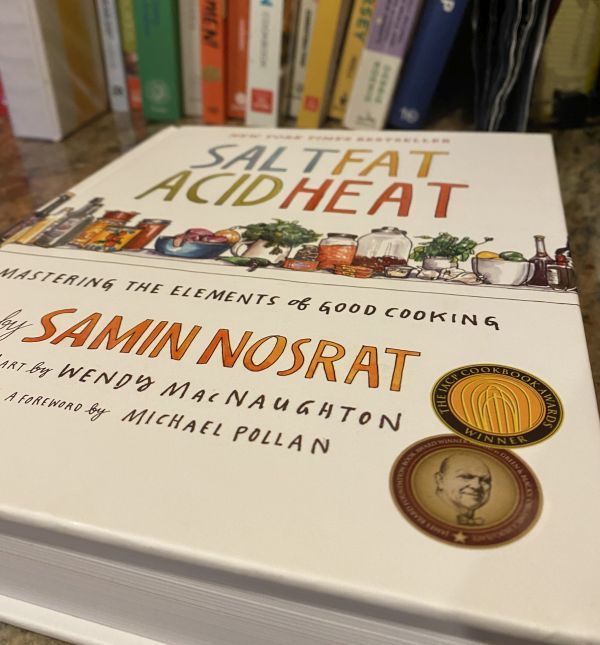

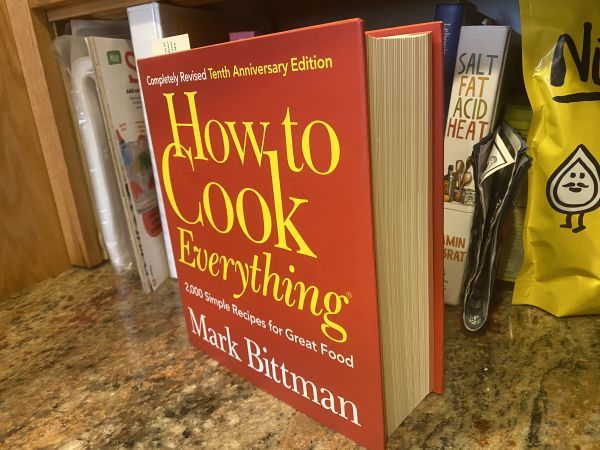

This is how it goes: I crack an egg into a small bowl, pour in a splash of milk, and tap in salt and pepper. The milk spirals out in trumpet-like hibiscus blooms before I beat it all together with a fork. Then I slide boneless chicken breasts in and out of the bowl, pulling them sleek and glistening onto wax paper. With a flick of my wrist, I cover each slice of chicken with breadcrumbs, using the outer edges of my hands to tenderize the meat. After this, they go into the skillet, sizzling in oil for two minutes on each side before being lined up on a baking sheet. We’ve always called the sauce “special sauce,” even though it’s just lemon juice, crushed garlic, parsley, and cooking oil from the frying pan. No matter. It’s special to us. I drizzle this mixture over the chicken cutlets before sliding the baking sheet into the oven, cooking it at 350 degrees for 15 minutes. My mother used to make this dish anytime we had company, as did her mother before her. And though I was always resistant to my mom’s cooking lessons when I was young, this dish feels like part of my DNA. Chicken cutlets aside, my childhood stubbornness has turned me into an adult who is completely beholden to recipes. I work my way through cookbooks, slotting winning dishes into a spreadsheet of my own creation, one that has tabs for each course in a meal. And once I have wrung all I can out of a cookbook? I buy a new one. Otherwise, things start to feel stale. There is not an intuitive bone in my body. I’ve heard that other people compare and contrast recipes for a single dish, taking the bits that seem right to them and making the dish their own. Or they perfect basic cooking techniques and pull together a meal with nary a recipe in sight. But I am so tied to recipes, I feel as if I cannot alter them in any way. I just wouldn’t know how. If a recipe ends up a disaster, I throw out the whole dish and never attempt it again, in any form. My most rebellious act in the kitchen might be to leave out the celery when making soup (god, I hate celery). Beyond that, I treat recipes as set-in-stone instructions for The Way Things Must Be. But I want so badly to be different. I will say, however, that when I first picked up this book, the lack of specific ingredient amounts or cooking times terrified me. 😱 The first “recipe” I attempted from this cookbook was one for egg drop soup. First, I made a brisket broth by boiling a whole-ass hunk of brisket in a large pot of water seasoned by wishes and magic and rainbows (meaning: I totally guessed how much salt and scallions and what-have-you to include; this is called cooking “to taste”). Then, I tossed in “a handful” of rice cakes (god save me from ingredient quantities like “handful,” “glug,” and “splash”), some additional chopped-up scallions, and an amount of soy sauce I will not even attempt to quantify. Later, when I beat an egg and poured it into the whirlpool of water I’d created with a wooden spoon, I watched with amazement as it unfurled into something that looked very much like…egg drop soup. The results were pretty damn good. The next week, I tried it with chicken stock instead, boiling a whole-ass chicken, getting even more cavalier in my seasoning of the broth. My success with this dish was so surprising to me, I began to think that maybe these kitchen renegades were onto something. I’ve since made a number of dishes from this book that I consider keepers. I’ve pre-seasoned ground beef to make dumplings. I’ve done stir-fry veggies of various sorts. I’ve made scallion oil noodles that my daughter and I are obsessed with. Last week, I made a tuna pasta salad and added chopped-up green olives. JUST BECAUSE I FELT LIKE IT. I am now drunk with power and you cannot stop me. Cooking techniques and ambiguous recipes aside, I think what I most appreciate about this book is how it taught me to tune in to the flavors I most enjoy and to lean into those preferences by getting creative with what I add to each dish. In fact, there’s a whole section early on in the book about the authors’ favorite ingredients for seasoning and I have bookmarked the hell out of it. I now keep a pouch of umami powder in my pantry (made with shiitake mushrooms) and if you seek to separate me from this new love of mine, you will have to pry it from my cold, dead hands. I’m a sucker for a rainbow-colored chart, so I was primed to love this cookbook. Pretty early on, I felt personally attacked by this book. Nosrat demanded that readers toss their granulated salt tubs and their bottles of lemon and lime juice. She told me my olive oil was crap. I am a person who buys parsley flakes and bottled fruit juices because I am lazy. I am a person who buys olive oil in a big, plastic bottle because it is cheap and easy to grip. But Nosrat was not about to let me get away with that. If nothing else, Nosrat’s voice in my head when I’m choosing things at the market has been enough to elevate my game. But there are also other things. Small things. Things I wonder if everyone but me already knew. Things like pre-salting your food (for which she includes a handy-dandy rainbow-colored chart on when to season various types of foods). Things like pre-heating your pans before you throw in your fat of choice. Like Chang and Krishna, she also spends a good amount of time on the various sources of fat and the various sources of acid from which one can choose, and she explains what each choice adds to a dish. I’m in love with the color wheels she includes that show the different types of fats and acids used around the world. And of course, she has pages and pages (and pages) of techniques for things like achieving crispness and achieving or retaining creaminess and braising or roasting something to the perfect level of doneness. All things I’ve never gotten a feel for because I just follow recipes without much thought, throwing up my hands in exasperation if something isn’t cooked well after I’ve cooked it for the exact amount of time and at the exact temperature I was told. I’m still working my way through the book, but I’ve already found success with it. Just last month, I got a bit cocky and decided to make the dish I love ordering most when going out to Italian restaurants: linguine alle vongole. I can’t even with these adorable illustrations. ANYWAY. Since my favorite restaurant closed and then reopened with new owners and then switched back to the original owners and then, um, burned down…I’ve been looking for a linguine alle vongole I love as much as theirs. And I have not succeeded. So, against my own misgivings that some things are just best when someone else makes them for you — someone who knows what they’re doing — I gave it a go. I even bought fresh parsley. It turns out the best linguine alle vongole I can find is in my own kitchen. Even as I was eating it, though, I was thinking: Hmmm…it could use a little bit more of this and I think I’ll definitely use less of that next time… Who even am I anymore!? It brings me joy that I can make one of my favorite dishes in my own kitchen. Now, I rinse my clams and I pre-heat my pan and I throw in a splash of oil, some onion ends, and parsley and I lay my clams in gently, placing the lid on top and waiting for them to open. Nosrat writes that “some of the stragglers need a little encouragement, so tap them with your tongs if they’re taking too long” and I don’t know why, but I love this. After removing all the clams but those last stubborn few from the pan, I now tap them gently while legit talking to them, encouraging them to open on up. The moment they gape wide, like baby birds gasping and grasping for their mother, is a delight. I get such a kick out of it. For someone who’s been sleepwalking through the same old recipes for the past few years, this new ability to futz and explore and play with my food — and with how it comes together — has made cooking fun again. Each dish now carries endless possibilities. This book contains basic cooking techniques for just about any type of food, sort of like that old classic, Joy of Cooking. Now that I have a basic grasp on some of the most important elements of good food, this book can help me get a handle on ingredients I don’t use very often, or ingredients I’ve struggled with in the past, allowing me to throw them together into full meals that get me excited to sit down to dinner. With practice, I won’t have to reference the book at all. With practice, every dish will feel as instinctual as my mom’s breaded chicken cutlets with special sauce. If you love the thought of being an intuitive cook, but still don’t want to give up that rush that comes with opening up a new cookbook, check out these 8 new cookbooks that will level up your cooking skills.