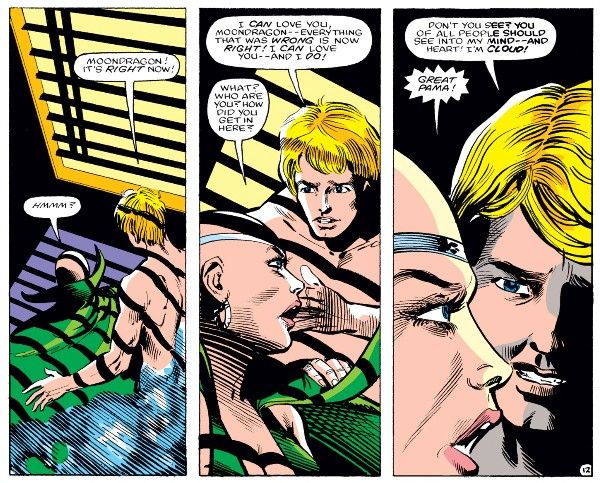

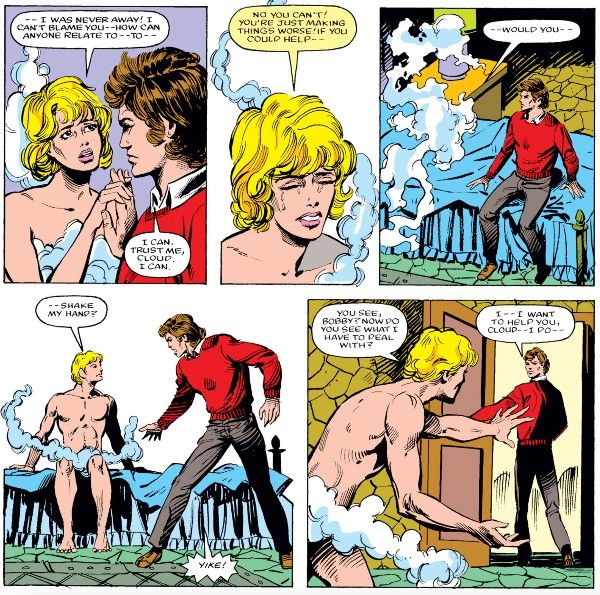

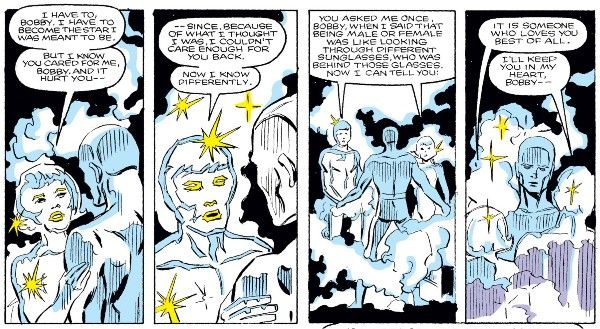

As I discussed in our first profile on Extraño, it can be hard to put queer characters in comics in any kind of chronological order, since many were introduced long before they were acknowledged as queer. Such is the case with Cloud, who debuted in 1983, but who was not canonically acknowledged as belonging to the LGBTQ community until last year. I chose to start our series with Extraño in 1988 because the creator intent and reader experience were both very clear in that case, but regardless of how Cloud was intended to be perceived in 1983, there’s no denying that sometimes they present as male and sometimes they present as female — and that’s been the case almost since their debut. So let’s take a look at the first trans/nonbinary character in comics! (In the ’80s, Cloud’s pronouns changed with their presentation, but I’ll be using they/them pronouns as those are the character’s current pronouns. Given that we’re talking about comics from the early ’80s, these issues also include transphobia and homophobia, both external and internalized.) Cloud debuted in The Defenders #123 (June 1983) and was created by J.M. DeMatteis and Don Perlin, though the bulk of their Defenders appearances were written by Peter B. Gillis. Originally, they took the form of a teenage girl — a completely naked one, made Comics Code-compliant by little wisps of cloud hovering around their chest and pelvis. Sigh. Cloud was originally presented as a minor antagonist for the Defenders, working for the evil Secret Empire. Eventually they are revealed to be a victim of brainwashing by the Secret Empire, and defect to the Defenders, where they become particularly close with both Moondragon and Iceman (Bobby Drake). However, Cloud is increasingly tormented by their growing love for Moondragon, which they fear is “wrong.” They solve this problem by abruptly changing into a male body (and still only shrouded in a little bit of pelvis-vapor, so that’s fair, I guess). “I can love you, Moondragon — everything that was wrong is now right!” they declare. Needless to say, their teammates are surprised by the sudden change, since no one knew Cloud had this ability — Cloud included. (Moondragon in particular is surprised, since she was sending out telepathic subliminal messages to make her male teammates fall in love with her for Reasons, and didn’t expect them to work on Cloud. It’s messy.) Mostly, though, the team takes it in stride, with the exception of Bobby, who is very uncomfortable and pretty much a jerk about it. Cloud spends a few more issues shifting back and forth between genders, primarily defaulting to female, until finally, in #150, we learn that Cloud isn’t human at all: they are a sentient nebula. Comics, everyone! Cloud, it seems, was just minding their own business out in space when they noticed the stars around them were disappearing. They fled to Earth in search of help, where the first humans they encountered were a teenage couple driving in a car. Cloud attempted to make contact with the teenagers, but the car crashed — it’s unclear whether this was Cloud’s fault or not — and the intense pain they felt upon attempting to communicate telepathically with the injured teenagers caused them to a) develop amnesia and b) shapeshift into a duplicate of the teenage girl’s body — but eventually, also the teenage boy’s. (Also somewhere in there the Secret Empire showed up. Look, comics aren’t here to make sense.) Upon realizing the truth, Cloud leads the Defenders in a fight against the threat that was destroying the stars, which isn’t at all relevant to our purposes here so I’ll skip it. Suffice to say that the day is saved, at which point Cloud decides to return to space to eventually evolve into a star. Let’s talk about the context all of this was published in. As I mentioned in Extraño’s profile, the Comics Code forbade queer characters until 1989, though that rule, like many in the weakening Code, was being tested here and there. Still, it was only in Fantastic Four #251 (February 1983), just a few months before Cloud’s debut, that the word “gay” was first used in mainstream comics, at least in the context of sexuality. Extraño was five years in the future, and anyway he would be published by the Distinguished Competition (aka DC). As far as the state of queer representation at Marvel went…well, that’s a big can of worms, the opening of which is probably best saved for our upcoming Northstar profile. Suffice to say it wasn’t great. All that said, The Defenders under Gillis’s pen is a deeply, deeply queer book, and Cloud is a huge part of that. Of course, I say that with the benefit of a 2022 perspective, when both of the characters Cloud is romantically linked to — Moondragon and Bobby Drake — are canonically queer. Moondragon’s lack of interest in Cloud’s male form hits different when you know she’s a lesbian, you know? Meanwhile, Bobby displays intense discomfort with Cloud’s male body, which today reads as repressed, self-loathing attraction, further eroticized by the fact that both of them are essentially naked in most of their scenes — Cloud in their fog-wisps, Bobby in his little ice-undies. Even Valkyrie, who stands up for Cloud when Bobby is being a jerk about their shifting gender, would eventually be canonically bi. It is not the most stunningly heterosexual comic imaginable, is my point. But was it intentionally so? After all, ostensibly the narrative purpose of Cloud’s gender fluidity is to make things less queer. Cloud is attracted to Moondragon, a woman, so they must have a male body in order to pursue her. Bobby is attracted to Cloud, but only if Cloud is a girl, of course! It’s also worth noting that the idea of changing one’s physical sex due to comic book-y science and/or magic had been around for a long time at this point. The very first comic book supervillain, the male mad scientist Ultra-Humanite, transferred his brain into the body of a female movie star in 1940, after which point the character’s pronouns became basically dealer’s choice. Now, please don’t think I’m declaring the Ultra-Humanite a trans icon or anything like that, especially since he’s been in the body of an albino gorilla since 1981. (Comics!) My point is really the opposite — that science fiction or fantasy changes to biological sex had been present in comics for decades, but not seriously linked to gender identity or sexuality. Gender and sex were largely presented as inextricably linked, and strictly binary. Cloud is an even more obscure character than Extraño, so I wasn’t able to find any direct quotes from Gillis or anyone else involved with the book at the time about their intentions, though this article says that “Cloud was created to specifically address, from a fantastic angle, actual trans experiences…[Gillis] had a friend who was at the time transitioning.” Sadly, it’s unsourced, so I can’t find any confirmation from Gillis directly. But The Defenders is so queer that I find it hard to believe that it could all be unintentional. Like. Cloud tells Moondragon they love her, on-panel, when as far as the reader knows at that point, Cloud is a cis woman! That alone should have been forbidden by both the CCA and Marvel editorial policy at the time, but somehow snuck through. And though some of the language used to describe Cloud, as well as their own self-loathing, is dated and uncomfortable to read today, the series never wavers from the perspective that Cloud deserves respect and acceptance regardless of their body or gender. That alone makes me lean towards the side of “Gillis knew what he was doing.” After returning to space in Defenders #150, Cloud pretty much disappeared from comics for over three decades, aside from a single panel cameo in 2011. They finally returned properly in last year’s Defenders series, where their physical form remains deeply fluid — male, female, adronynous, nebula. They also state that their pronouns are they/them — the first time that’s been the case for them in canon. It’s too early to tell if Cloud will continue to appear in modern comics. I hope they do: they are sweet and likable, with a cool power set, and it’s not like the Marvel universe is overflowing with nonbinary representation without them. Either way, I’m glad they got to return recently and make their pronouns and identity clear in a way that they couldn’t in the ’80s — and I’m glad that even back when it was officially forbidden, some diverse representation, intentional or otherwise, managed to slip in through the cracks.