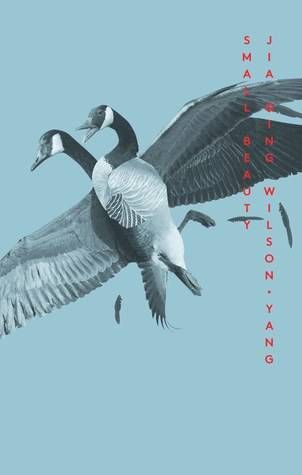

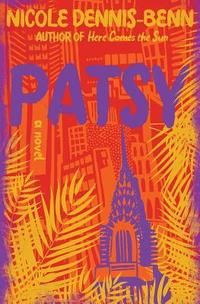

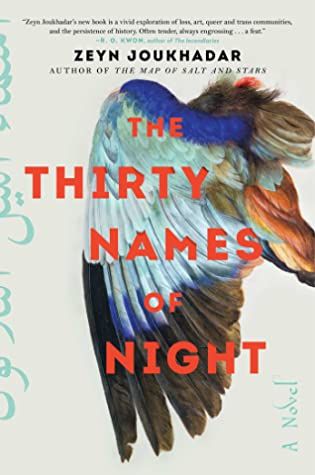

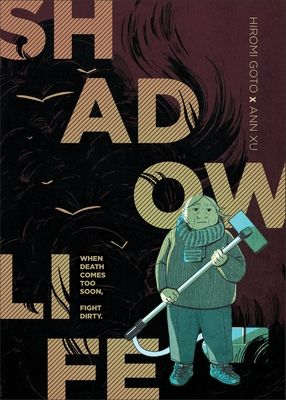

The authors of these books understand that being a queer parent is actually different from being a straight parent. They understand that queerness changes parenthood. At the same time, the queer parents in these books are often engaged in acts of parenting that have nothing to do with being queer: breastfeeding a newborn, or trying to get your overprotective adult daughters to leave you alone. Queerness always matters, but not always the same amount. So, without further ado: five novels featuring queer parents in all their flawed and human glory. This is a book full of queer characters who mess up, make mistakes, act selfishly, cause each other harm, offer and receive forgiveness. Their queerness changes who they are as parents, and parenthood also changes how they understand, express, and relate to their queerness. It’s a stunning and deeply layered novel, and one of the most honest depictions of queer parenthood I’ve ever read. Patsy is not a perfect mother; far from it. She’s a Jamaican lesbian who leaves her young daughter, Tru, in Jamaica when she emigrates to the U.S. She leaves, partly, in search of her best friend and first love, Cicely. Queerness is obviously not incompatible with parenthood, but right from the start, Dennis-Benn shows she isn’t afraid to explore how queerness and parenthood can clash, especially in a homophobic, sexist world. Patsy wants to live a free life as a queer woman, and she decides to leave Jamaica to do so. She makes a choice that harms her daughter. She does it for herself. Over the next decade, as Patsy and Tru live lives apart from each other, we get to see all the various consequences of Patsy’s actions. There’s joy, freedom, pain, loneliness, love, despair. It’s a story full of contradictions, about deeply flawed people in impossible situations. It’s rare to find a book staring a queer mother as fully alive as Patsy is. This is the kind of book about motherhood I needed when I was in my early 20s. It’s not a rosy picture of a mother-daughter relationship — it’s an honest, vulnerable, and deeply human one. The story unfolds in two timelines. In contemporary New York, Nadir, a twentysomething Syrian American trans man, is grieving the death of his mother, taking care of his grandmother, and beginning to come out. He discovers the journal of a Syrian bird artist that his ornithologist mother loved, Laila Z. Half of the book is told through Laila’s journals, as she tries to build a life for herself as a queer artist and immigrant in the 1940s and ’50s. As Nadir learns more about Laila, their stories — the stories of their family and community — begin to intersect. Like in Small Beauty, watching Joukhadar masterfully weave these queer and trans lives together is part of the absolute joy of this novel. What I’ll say is that he exuberantly writes queer and trans people into so many kinds of familial roles: parents, grandparents, children, siblings, aunties. It’s a breathtaking novel about queer lineage, and the power of queer and trans people sharing their own stories with each other. This is such a charming, funny, heartfelt story. Kumiko is bisexual, and though her queerness isn’t central, it’s important. Kumiko’s husband is dead and her adult children are a real thorn in her side. So when Death comes for her, the person she turns to for help is her ex, the woman she dated before she got married. This felt so natural to me, so familiar. It happens all the time in queer communities. We turn to one another for support, especially when we can’t find it elsewhere. I also love that Kumiko’s daughters don’t find out she’s bi until they meet her ex, near the end of the book. It didn’t feel like Kumiko had been hiding anything on purpose. There was no dramatic reveal. Rather, through Kumiko, Goto is exploring the idea that parents have lives outside of their children. Kumiko had a life before she became a mother, and she has a life in old age beyond being a mother. The whole novel is a beautiful portrait of the many lives a person can lead. Sometimes those lives blur and blend, and sometimes they don’t.